Firmly in their sights is the longstanding question that has perplexed the wheat research community: Why do grains at the bottom of the spike fail to achieve full size compared to those higher up?

Previous studies have analysed wheat tissue in bulk (taking dissected tissue pieces in their entirety), limiting image resolution, and increasing the likelihood of unclear results.

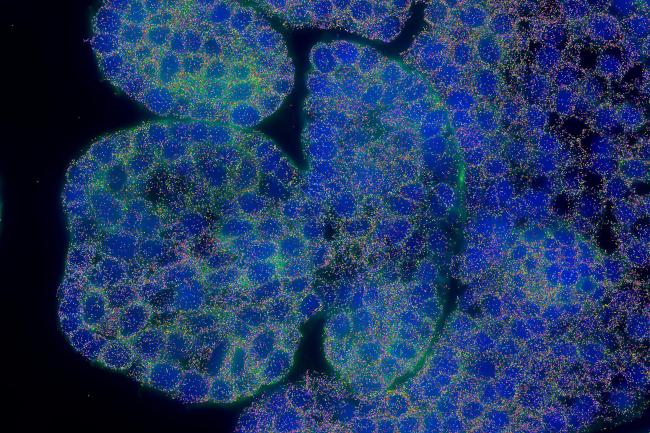

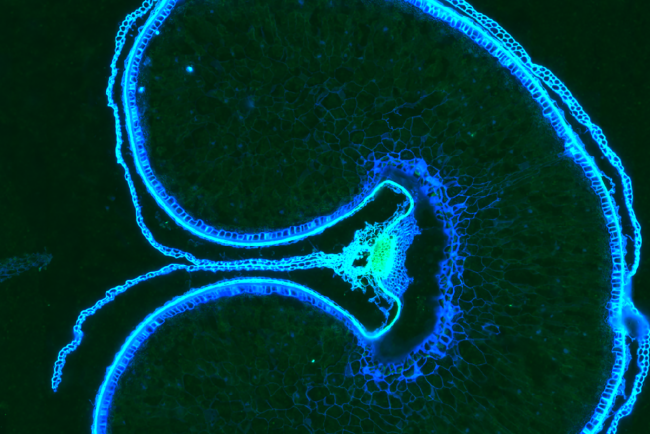

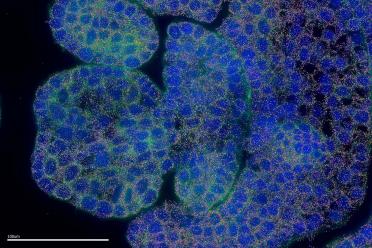

Published in The Plant Cell, the collaboration applied spatial transcriptomics, a powerful, emerging technology that visualises tissues at single cell resolution in situ, so that they can be observed fully in context of their location in the plant.

The technique is fraught with difficulties because plants have very tough cell walls and are prone to produce fluorescence which obscures results. Despite the challenges, the research team successfully mapped the expression of 200 genes in a set of wheat spikes at different development stages.

Their findings reveal highly distinct expression patterns across spikes, information which will help answer why basal spikelets (the structures at the base of the spike) often only produce rudimentary structures instead of harvestable grain, even though they are the first to form during development.

2.5 billion people depend on wheat as a source of food and as global populations grow, demand is expected to rise by over 60% by 2050. By offering a blueprint as to how the wheat spike forms, the study will be crucial to improving wheat yields as scientists worldwide race to increase crop productivity.

A key priority was ensuring the data remains open access and available as a resource for future research and industry. To facilitate this, the team created a new platform where researchers worldwide can access and build upon these findings.