The study in the journal PNAS addresses longstanding questions in biology: Can plants sense the environment directly in their developing seeds, or is seasonal information acquired by their parents somehow passed down to the seed?

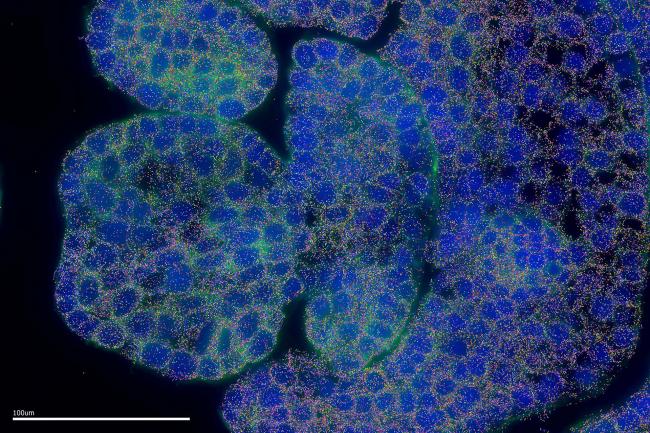

To investigate this, researchers took advantage of advances in single cell technology that enable molecular analysis of cells both individually and within the context of their tissue environment, in situ.

They applied this developing technology to tissue samples of Arabidopsis thaliana, a ‘model’ plant with both male and female reproductive organs.

They found that absisic acid (ABA), a plant hormone, increases in specific plant maternal reproductive tissues when the temperatures drop.

In these cooler conditions this hormone, a plant growth inhibitor, is sent early to the developing seed at a higher rate, helping it to enter dormancy (the ‘sleeping state’ that prevents seeds from growing until environmental conditions are favourable for their growth.)

In warm temperatures, beneficial to successful seed germination, researchers observed that ABA does not peak early but builds steadily, playing less of a role in inducing seed dormancy.

Other non-maternal tissues showed little or no change in ABA with temperature. Further experiments showed that mother plants unable to produce the hormone were unable to induce a dormant response in their seeds.

Together, the experiments reveal a mechanism by which developing seeds receive recent seasonal temperature and nutrient information from the mother plant, in the form of ABA.

The research is a key contribution to the debate about how long it takes plants to adapt to climate change. The message from this study is that, to some extent, they can adapt almost immediately because they are pre-adapted by their mothers to the environment they are dispersed into, using fast-track hormonal messaging.

By highlighting how hormonal transport can influence traits from one generation to the next, the study introduces a vital new tool, alongside genetic and epigenetic inheritance, for researchers and breeders looking to develop climate smart crops.

The research may also help address a big problem in agriculture relating to germinability – a seed's ability to sprout in a timely way that leads to more predictable yields for farmers. Using the knowledge gained in these experiments may enable the development of seeds better adapted to their local environment in which the mother plant grew.